Like previous summers, I threw my essentials into the car and drove west towards the mountains. This time, my compass pointed towards even bigger mountains–always bigger mountains is the trend. Alaska. 4000 miles, 15 states, and one speeding ticket later, I am situated in my temporary home base for the summer on Douglas Island, a walk over the bridge from Alaska’s state capital, Juneau.

Like previous summers, I threw my essentials into the car and drove west towards the mountains. This time, my compass pointed towards even bigger mountains–always bigger mountains is the trend. Alaska. 4000 miles, 15 states, and one speeding ticket later, I am situated in my temporary home base for the summer on Douglas Island, a walk over the bridge from Alaska’s state capital, Juneau.

Sometime back in the fall I got the idea in my head that I’d drive to Alaska for a summer job. At the time, I could hardly take the thought seriously. But after a few interviews, I took a job with Alaska Heli-Mush, a high end sled dog tour kennel on the Norris Glacier in the Juneau Icefield. So I hit the road with my good friend, Faraday. The long drive to work gave me a lot of time to think about what to do without Hampshire College on the fall horizon. The new freedom is exciting, but also overwhelming. I ended the trip with more questions than I started with, but also explored some philosophical territory that provided insight into them all.

So we took to the road, stopping at some of the most beautiful places we had ever seen. But even better than the scenery, were the people we met along the way. We spent our first evening with our friend Martin and his family outside of Detroit. They gave us a place to stay and some good food to eat after a long day of driving. I even got to sing some Polish Christmas songs with his mom (don’t ask) and saw Martin make a pretend machine gun out of his oversized fur-ball cat, Celka.

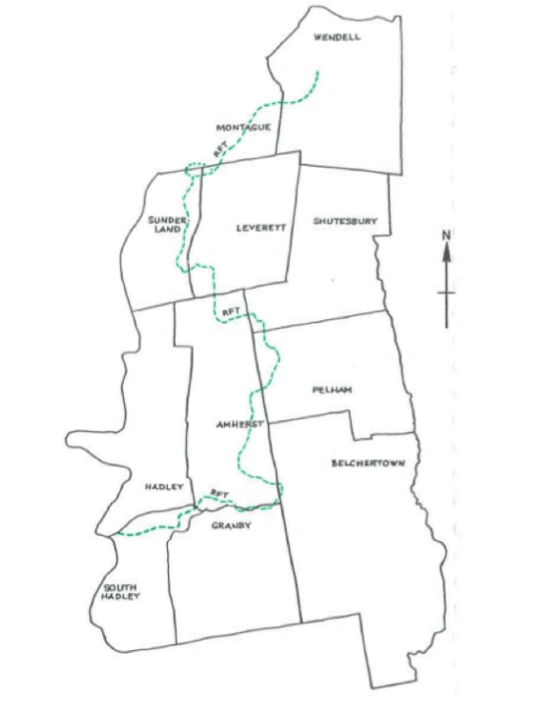

As we got further from home, the conversations we made with others from familiar eastern states provided much comfort in the new landscapes we were experiencing. Simply being from the eastern states was enough to start a conversation, even if the distance was from Massachusetts to Washington D.C. or even Florida. There was the Sinclair family. We met them at the Liard Hot Springs in northern British Columbia during their trip up the Alcan from eastern Massachusetts to Anchorage, Alaska. They had both just retired and were taking up residence in the great state of Alaska. From just our short parking lot conversation, I was offered a place to stay if I ever passed through Anchorage.

And the transient look into the lives of those who lived elsewhere in the vast North American countryside, whether through simple observation or engaged conversation, proved that we have more in common than not despite our physical distance. I had learned that truth in Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley: “Americans are more American than Northerners, Southerners, Westerners or Easterners . . . California Chinese, Boston Irish, Wisconsin Germans, and yes, Alabama Negroes, have more in common than they have apart . . . It is a fact that Americans from all sections and of all racial extractions are more alike than the Welsh are like the English, the Lancashire man like the Cockney, or for that matter the Lowland Scot is like the Highlander.”

After spending some meditative alone time in the hot springs, I began talking to some folks from Edmonton, Alberta about the Athabasca tar sands, the dirty extraction process, and our energy future. I learned that they were on the road traveling to Dawson City, Yukon for a friend’s funeral, adding more friends and family to their caravan as they made their trek north. Unlike most others traveling the AlCan, they, like ourselves, were not RV-ers. Just a sidenote–despite being on the road with so many RV-ers, we hardly made any conversation with any of them. They mostly found other RV-ers to talk to about RV stuff. From Liard to Whitehorse, Yukon, we ran into our Edmonton friends 5 times in two days at rest stops and in towns. In Whitehorse, we found them on the side of the river cooking burgers, more friends in tow. By this point, although we didn’t know them by name, we picked up conversation like they were good friends. They offered us some of their food and suggested some good camp spots. They made us feel a whole lot closer to home. All of the friendly strangers did. It was exactly what I needed to experience before starting work far from home.

The trip provided a smooth transition away from college towards “adult life,” plus, Faraday and I were able to get caught up on our favorite podcasts, This American Life and the Dirtbag Diaries.

Trip Highlights: crossing into Canada, Banff and Jasper National Park, seeing many grizzly bears, including a mother and three cubs, several black bears, mountain goats, moose, elk, antelope, bighorn sheep, a Canadian lynx, mule deer, tons of eagles, meeting so many kind people, the Liard Hot Springs, AlCan Highway, traveling through new places, climbing at Bozeman Pass, the Bee’s Knees Hostel and Nancy and Bertha in Whitehorse, crossing into Alaska, Janilyn and the Alaskan Sojourn Hostel, Keith and Brandon (some awesome travelers with some good stories)

Avalanche Lake in Glacier National Park

Met a guy here named Jesse from Pittsburg who lived in Juneau for three years.

Driving through Jasper, Alberta

typical roadside dinner

“Welcome to Yukon”

Can only imagine what happened here.

Sign Post Forest. Signs from all over including Springfield, MA. The signs were a reminder of the awesome places in the world.

And into Alaska

Trip Highlights:

crossing into Canada, Banff and Jasper National Park, seeing many grizzly bears, including a mother and three cubs, several black bears, mountain goats, moose, elk, antelope, bighorn sheep, a Canadian lynx, mule deer, tons of eagles, meeting so many kind people, the Liard Hot Springs, AlCan Highway, traveling through new places, climbing at Bozeman Pass, the Bee’s Knees Hostel and Nancy and Bertha in Whitehorse, crossing into Alaska, Janilyn and the Alaskan Sojourn Hostel, Keith and Brandon (some awesome travelers with some good stories)